Summary

- The world is changing – and European governments are struggling to decide how to position themselves within it.

- Middle powers outside Europe are preparing for a fragmented, not a bipolar world, and approaching the emerging order with some confidence. The EU can learn a great deal from their strategies.

- The EU has a myriad of interdependencies with other powers and will never be totally self-sufficient. To protect its interests and values, it needs a foreign policy strategy that acknowledges this: strategic interdependence.

- The EU should anchor this approach in an understanding of where it needs partnerships – and the potential power it wields within them.

- It should prepare for political coexistence and competition, privilege de-risking over decoupling, and invest in key relationships rather than in defending the old order.

The post-cold war order is dying. But the new order has not yet been born.

The growing geopolitical competition between the United States and China has inspired many to imagine that a new cold war will soon structure the emerging world order. According to that vision, the competition between two nuclear superpowers across every domain will in essence determine the global order. US president Joe Biden’s effort to divide the world into democracies and autocracies betrays an instinct to fight the current global struggle much like the last. A consequence of this could be a great decoupling that marks an end to the economic interdependence between China and the US, which could then become the patrons of two blocs defined by ideology.

Both the US and China assume that in such a global order, Europe would neatly align with the US as part of the West. But it is for Europeans to determine their own strategy.

During the long years of the cold war, most countries had little choice but to align themselves with one bloc or the other. Even those countries that managed not to choose sides nevertheless defined their identity in reference to this central struggle of the cold war, forming a “non-aligned movement”.

But today’s world is not the one of 1945. A new cold war, or for that matter, an actual war, is a possibility, but it is not a global destiny. Today’s superpowers, as powerful as they are, lack the level of dominance that the US and the Soviet Union had achieved at the dawn of the cold war. In 1950, the US and its major allies (NATO countries, Australia, and Japan) and the communist world (the Soviet Union, China, and the Eastern Bloc) together accounted for 88 per cent of global GDP. Today, these groups of countries combined account for only 57 per cent of global GDP and are all having to compete with new players in emerging fields of power such as tech and climate. Non-aligned countries’ defence expenditures were negligible as late as the 1960s (about 1 per cent of the global total), but now they are at 15 per cent and growing quickly. In regions in which the US and China have long invested to build up strategic relationships – including the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America – neither player is able to assert unequivocal dominance.

Moreover, neither China nor the US has the type of inspiring ideology that in the cold war helped move elites and publics throughout the world into strict alignment. China today merges a communist ideology with many capitalist elements in its economy. Meanwhile, the traditional American vision of liberal democracy as a universal value has been tarnished by the abuses of the unipolar era, particularly the Iraq war, and by the autocratic excesses of the Donald Trump presidency. China and the US are engaged in a contest for geopolitical supremacy and are willing to use all tools available to that end. But, without an ideology to define and bind the blocs, countries can more easily operate without aligning themselves to one of these patrons.

The competition between a Chinese-led bloc and an US-led bloc will therefore not define the emerging world order. A new class of middle powers has much more agency than they had during the cold war. These countries are engaged in acquiring their own influence in international affairs and are willing to leverage US-China competition to their advantage or, in many cases, challenge it. Their decisions on their relationships with the superpowers, and with each other, will largely determine where the new world order lands on the spectrum from bipolarity to fragmentation. If collectively these powers choose to align with one or the other superpower, then we may indeed have a new bipolar confrontation. If they opt instead for more promiscuous strategies that seek to avoid strict alignment, we will get a much more disordered landscape.

This paper argues that middle powers are shaping a more fragmented world, characterised by an increasingly transactional approach to foreign policy, for which Europeans are ill prepared. It then sets out a strategy, informed by an analysis of the behaviour and priorities of a selection of middle powers, for how the European Union can defend its interests in this emerging world order.

The middle power way

This paper takes a broad definition of middle powers, including such diverse countries as India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Kazakhstan, South Africa, and Turkey, to reflect the fact that a wide range of players is shaping the new world order in different ways. Overall, they have no single common feature that defines them as a group, except an approach to foreign policy aimed at maximising their sovereignty as opposed to subscribing to any specific ideology. They often pursue this similar goal of increased independence using quite distinct strategies. In the context, for example, of Russia’s war on Ukraine, this concern for state sovereignty drives both alignment and non-alignment with the West depending on the strategy of the given middle power. A prerequisite for understanding the coming world order or disorder is thus a thorough understanding of the diverse middle power actors on which it depends.

The picture that emerges from such an analysis is not one of a bipolar world or even a well-defined multipolar order. Some powers define their foreign policy strategy against the superpowers. Singapore, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, and others are focused on stopping China from becoming a hegemonic power and preserving stability. Many countries in Latin America or the Gulf on the other hand, which long existed in a US sphere of influence, are now trying to hedge against that overdependence by building relationships with different powers, and China in particular. But middle powers do not only define their foreign policy strategies in opposition to the superpowers. A central feature of strategic thinking in former colonies and former members of the Soviet Union is how to lessen ties with their former masters by building up relations with everyone else. Some of these countries – such as Egypt – have long been non-aligned countries and are reinventing this position for a new age; others – such as the central Asian countries – are building non-alignment for the first time. Meanwhile, pragmatic players, such as India and Turkey, are motivated by the aim of being friends with all and vassals of none.

Europeans stand apart in this analysis. Many European countries are significant powers in their own right, and the EU as a whole has the potential to compete more or less on par with China or the US. But the EU is not a nation state and cannot fully realise that potential in its current institutional configuration. Various Brussels buzzwords, like “strategic autonomy”, demonstrate a desire for greater independence from the US along the lines of most middle powers. But despite their latent power, EU member states currently cleave closely to Washington in their foreign policy strategies. This of course reflects Europe’s shared values and historic relationship with the US. And, as the war in Ukraine has demonstrated, the transatlantic relationship remains central to the defence of Europe. European rhetoric largely demonstrates a deep and continuing attachment, even a nostalgia for the American-led order. Europeans remain the most reliant on the American idea of a rules-based order built on liberal values in defining their engagement with other powers.

This narrative, based on European values rather than interests, defies the trend in many other global regions. It also leaves the EU wide open to the challenge that in actual EU policy, in fields such as immigration and carbon pricing, it does not practise what it preaches. And it fails to tackle the reality that it is not only great powers that will play a critical role in defining the new world order.

The EU has complicated interdependencies with a variety of actors. When it comes to energy, untangling itself completely from an over-dependence on Russia is its biggest problem. To secure the rare earth metals and other minerals that are crucial to the green energy transition, Europe will need to reckon with and, simultaneously, compete with China in other regions. At the same time, there will be occasions when it defines its interests differently from the US. Whether or not it emerges as a formative player in shaping the new world order will depend on member states’ political will to work together to manage their complex interdependencies, and to adopt a more strategic approach to protecting their interests in the shifting geopolitical landscape in the way that other middle powers are doing.

Europeans should not limit their preparation to a new cold war scenario – because all other middle powers are preparing for, and shaping, a much more complex order. They are interested in cooperative relationships with a variety of other powers, including the EU. And, given their significant weight and resources, they will increasingly succeed at having them. The weaponisation of migration management by Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, and a range of other African states to win concessions from Europe underlines the extent to which the distribution of power is shifting.

In this new, more fragmented world order, the EU needs a strategy that stresses its connections with countries beyond the US in order to protect its interests. This approach to foreign policy should not define the EU in opposition to or in league with either the US or China, but rather allow it to both cooperate and compete with other players as appropriate, based on a clear understanding of its interests, and in respect of its values. In essence, this requires it to learn from the approaches of the middle powers.

A taxonomy of middle powers

To build a more strategic approach to interdependence, Europeans have much to learn from the middle powers that are shaping the new order. With slight violence to the diversity of these countries, we have identified four basic groups:

The peace preservationists

Across the Indo-Pacific, the dominant factor reshaping the international order is the rise of China and its global economic, military, and political implications. It is the region in which the systemic competition between the US and China is the most palpable. Many of the countries in this region are therefore peace preservationists – focused on managing the rise of China as a hegemonic power and avoiding war. Indonesia is perhaps the clearest example, defining its own foreign policy strategy as “independent and active” and emphasising non-alignment, neutrality, and stability. It advocates respect for national sovereignty and territorial integrity, while also emphasising the need for dialogue, cooperation, and consensus-building among nations. Indonesia actively participates in various international organisations and platforms to this end. It has been a strong supporter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and plays an active role in regional diplomacy. Singapore is another clear example. Culturally and ethnically, Singaporeans have much in common with China (about 75 per cent have an ethnic Chinese background), economically the country is deeply dependent on China for trade, but the US is the largest investor. Singapore has kept a relative degree of independence in its foreign policy – it has joined Western sanctions against Russia, is training its armed forces on Taiwan, and has been a close security partner of the US. It offers a safe and stable environment for trade and technology development and has become a haven for investors worried about instability in the region.

Other powers in the region, such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, respond to the rise of China by aligning themselves closely with the US in an attempt to maintain the US-led order that ensures their interests. At the same time, in their economic and technological relationships, east Asian players are all highly dependent on China as a market and as part of their supply chains. They therefore see an absolute imperative in avoiding conflict between the US and China even as they accept they need to de-risk their relations with Beijing to some degree. The growing pressures emanating from escalating US-China tensions and the bifurcation of the technology landscape have led Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan to explore economic security strategies that shore up critical dependencies and to attempt to enhance supply chain security. There is an acute awareness among all three that the strategic, political, and regulatory choices of the US, the EU, and China will limit their own room for manoeuvre and their ability to make independent economic and strategic choices.

A possibly even greater threat emanates from China’s assertive behaviour and military build-up in the region, as well as that of its partners, North Korea and Russia. Challenges to established norms and rules may therefore have consequences for maintaining stability in the region. This realisation has led all three east Asian players to support US and European sanctions against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine. Japan already had sanctions in place following Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Indonesia on the other hand has not imposed sanctions against Russia, but has been willing to join resolutions on Russia’s aggression in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), and to provide humanitarian assistance to Ukraine. For the peace preservationists, the war in Ukraine is a test case for the seriousness of US alliance commitments and is clearly linked to a potential Taiwan contingency.

This has, in part, inspired the current rapprochement between Japan and South Korea, two powers with a historically fraught relationship. Japan has also been more outspoken than ever before in its commitment to support Taiwan. In general, the peace preservationists have been adapting their policies to support order on both the regional and global level, lest disorder come to them.

The America hedgers

These countries have traditionally belonged to the United States’ sphere of influence but are now trying to hedge against overdependence on the US by engaging with new partners. The energy potential of the two regions of the America hedgers that this paper explores – Latin America and the Gulf – means that they have growing leverage in their relations with larger powers.

The historical interventionism of the US has shaped Latin America’s foreign policy. During the cold war, the US often treated Latin America like its geopolitical “back garden”, pushing back hard if countries of the region risked the slightest flirtation with the Soviet bloc. The resulting policies, as well as the harsh economic adjustment policies of the Washington consensus, left a legacy of authoritarian regimes, polarised societies, and civil conflicts in many Latin American countries. Partially as a result, these societies often exhibit a notable strain of anti-Americanism.

In recent years, the US and the EU have turned their attention elsewhere, while China has actively pursued strong political and economic ties with Latin American countries and actors, and included the region in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Russia has also been increasingly active. China is now one of the major recipients of Latin American agricultural exports but also of critical minerals such as copper and lithium.

Most countries in Latin America nevertheless aspire to the values of liberal democracy and free-market economics embraced by the West. But they have not consistently aligned themselves with Western powers or established permanent security alliances, as Japan and South Korea have done.

Their reaction to the conflict in Ukraine demonstrates both their attachment to Western values and their reluctance to align with it geopolitically. They mostly voted to condemn the Russian aggression in the UNGA, but they have not supported Western sanctions, seeing them as just another episode in an east-west conflict, of which they have often been collateral victims. These countries therefore tend to practice an “active non-alignment”, seeking to preserve their strategic independence and avoid choosing sides. Their vision of the international order is dominated by a desire to exercise political and economic sovereignty and to avoid external interference, especially from Washington and Brussels. Brazil has departed from this policy of minimising confrontation and, under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has actively sought to shape the international order and give Brasilia a prominent role in it.

As a result, actors that are perceived as supporters rather than constrainers of national sovereignty, such as China, wield greater political influence among the America hedgers, even if their models of values, politics, and economics do not align with those in the region.

Other prominent examples of America hedgers include key Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which have grown doubtful of longstanding US security guarantees. They are now assertively setting their own agendas and pursuing transactional relationships with different global players in what they perceive as a multipolar order. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE increasingly consider themselves to be major shaping actors that no longer need to accept ‘diktats’ from outside powers. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting global scramble for allies and energy has solidified this view.

At part of this thinking, regional states are increasingly wary and seeking to avoid becoming entangled in great power competition. If the US tried one day to tighten the screws on China as it has done on Russia, it would seriously disrupt critical GCC economic ties. Saudi Arabia particularly cannot afford a scenario in which oil purchases from China – a critical driver of its domestic economic transition – dry up because it is forced to align with the US or comply with new sanctions.

But GCC states also do not want to put all their eggs in the Russian and Chinese baskets. Just days after Saudi Arabia and the UAE were invited to join the expanded BRICS forum this September, for example, the India-Middle East-Europe economic corridor (IMEC) – was announced. European states consider this plan to build a railway and, later, digital and electric cables, as well as a clean hydrogen pipeline, from India to Europe as a major step forward to rival China’s BRI, but from point of view of the GCC states, it should rather be understood as one element of their broader hedging strategy. Despite important political, economic, and energy relations with Moscow, Russia is now bogged down in a conflict that is making it poorer and pushing it into China’s arms. As with the Latin American hedgers, China’s allure in the region has benefitted from its policy of political neutrality and non-interference that privileges economic ties over geopolitics. But China could turn into a challenging partner if it invades Taiwan and becomes more geopolitically assertive, potentially provoking wider global conflict that would imperil GCC efforts to maintain relationships with all sides.

This new approach does mean more open defiance of some Western positions. GCC countries broadly accept the principle that Russia should not have invaded the sovereign territory of another country – and have mostly supported UN resolutions condemning the invasion. But they are unwilling to embrace the notion that this is a global war in defence of a global rules-based order. This is in part driven by self-interest to allow them to maintain important ties with Russia and China. They also consider this framing to be hypocritical given longstanding Western policies in the Middle East, such as in Israel-Palestine and during the Iraq war, where they see these values as little more than cover for the pursuit of Western interests.

The GCC’s unwillingness to fully embrace the Western coalition in defence of Ukraine, as well as the Saudi-led alignment with Russia as part of the OPEC Plus effort to maintain higher oil prices, reflects this positioning. The UAE, according to US officials, has emerged as a hub for Russian sanctions evasion and has also been expanding security ties with China. More broadly, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are both slowly exploring how they can avoid over-reliance on the US through de-dollarisation strategies, including by increasing transactions in other currencies. One example of this is the ongoing negotiations with China over the Petroyuan.

But Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s self-assertive path does not constitute an abandonment of Western actors, which they still look to as vital partners on key issues and interests. They have sought to position themselves as possible mediators between Russia and Ukraine and proved useful to the West on some fronts, such as facilitating a prisoner exchange deal with Russia. They also seem determined to maintain – and even strengthen – security ties with the US, which they still view as the dominant global security actor. For the GCC states, it is not a matter of choosing between the West and China but of maximising their autonomy to extract gains from both sides.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE appear to be confident that they can successfully navigate the competing pressures emerging from this approach, especially given that Western actors seem to have grown more tolerant of their hedging. Their role balancing between the different poles increases their political importance, while their immense energy resources and economic networks give them important material weight that they can leverage. Although the US has imposed some sanctions on Dubai-based entities accused of facilitating Russian sanctions evasion, the West’s wider response to GCC positioning in opposition to Western interests has been muted. Likewise, for China and Russia the Gulf monarchies are too important to press given their energy dependencies and the GCC’s ability to act as a network of global connectivity for sanctioned states.

Ultimately America hedgers are working to ensure that they no longer have to put up with a global order in which the US – or anyone else – can impose decisions on them. To a large degree, they are succeeding, with shifting dynamics providing new opportunities for the region to transactionally hedge between key global actors in a manner that prioritises and best advances their own political, security, and economic interests.

The post-colonial dreamers

This group includes former colonies in Africa and central Asia, which, like the America hedgers, are trying to throw off the yoke of their former colonial masters once and for all by building up relations with almost everyone else. Some have long been non-aligned countries and are reinventing this for a new age. Others are trying non-alignment for the first time. Unlike the America hedgers though, many of the post-colonial dreamers lack the wherewithal to challenge their former patrons outright.

The prevailing view in African states is that the existing world order is an expression of the deeper, inequitable power dynamics. Multiplying global crises such as the covid-19 pandemic and the climate emergency have hit Africa the hardest. Unlike the global north, poorer African nations lack the option of running up national debt or creating stimulus packages to buffer global crises. They therefore remain deeply reliant on international aid from all partners to weather such onslaughts.

To increase their self-sufficiency for future crises, African countries need to maintain existing patrons while drawing in new ones. A frontal assault on their range of historical, Western patrons in the manner of the America hedgers is not possible. Their primary strategy for strengthening their sovereignty is to demand greater representation in the leading multilateral global governance organs, which they believe underrepresent Africa and fail to deliver for the continent. They are driving, with some success, a discussion about a seat for Africa at the G7, as well as clearer representation in other forums, such as the Bretton Woods institutions and the UN Security Council, after the African Union became a permanent member of the G20 in September 2023. They justify this demand by stressing the inequity of the current system. African countries are also pursuing membership in competing multilateral structures dominated by the West’s rivals, such as the BRICS and the New Development Bank. In doing so, they kill two birds with one stone, expanding their array of partnerships beyond the West and putting additional pressure on the West to pursue reforms to other multilateral structures.

The attitude in central Asian countries towards world order is similar, though they have a different former colonial master, and their independence is much more recent. Like in African countries, leaders have a strong attachment to the independence and sovereignty that their countries achieved after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but also difficulties in asserting it. This attachment to sovereignty explains why none of them has been supportive of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Only Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have explicitly distanced themselves from Russia’s war, but none of the countries in the region voted against the UNGA resolutions condemning the war – they either abstained or did not take part in the votes – despite their historical attachment to Russia. None of them has recognised the annexation of Crimea in 2014; nor have they recognised the breakaway Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states.

However, the fear of Russian dominance in these states is balanced by a strong aversion to any form of Western “interference” in their internal affairs, especially regarding human rights, which could promote a democratic agenda that would undermine the grip of governing elites on institutions and resources. Central Asian countries may therefore choose to rely on foreign interference when in need of support, but they will likely prefer that of their authoritarian allies. Kazakhstan’s call for the support of its Collective Security Treaty Organisation allies to quell the domestic protests in early 2022 was a case in point.

Central Asian countries inherited infrastructure from their Soviet pasts that gave Russia a pivotal role in their connection to the rest of the world. Building up their sovereignty thus means attracting new players that are ready to invest to diversify their economy. Chinese investments particularly have been instrumental in creating new infrastructure, which has allowed central Asian countries to counterbalance their traditional dependence on Russia, but they have also been pursuing a more general diversification of their international partnerships, including by building relationships with Turkey, South Korea, and Gulf countries.

The spectrum of possible strategies is therefore much wider than merely choosing between Russia and China. Central Asian countries have developed various strategies to diversify their foreign policy options, with the overarching goal of consolidating their independence and sovereignty. These range from Turkmenistan’s isolationist neutrality to Kazakhstan’s bold effort to play on the global diplomatic stage and build strategic partnerships with actors such as the EU, as well as to the various hedging strategies of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The polyamorous powers

Unlike the America hedgers and the post-colonial dreamers, the polyamorous powers are not trying to defend their sovereignty against any specific country. As powers with a clear upward trajectory, they are confident enough about their role in the next global order that they are happy to enter into relationships with all manner of partners. Turkey, for example, finds itself in an open relationship with the West, while India is completely untethered and more than happy to play the field.

Overall, post-Western Turkey has issues with the current global order. It feels it deserves greater recognition of its sovereignty and security concerns from institutions of global governance and is increasingly uncomfortable with US primacy in the world order. This forms the undercurrent of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s frequent rants at the West and his sloganised criticism of the international order: “The world is bigger than five.”

Perhaps more than other middle powers, this new Turkey somewhat carelessly boasts about its regional influence and declares its global ambitions – couched ideologically in an odd combination of Turkish nationalism and somewhat old-fashioned anti-colonialism. It is not for nothing that Erdogan successfully campaigned under the slogan “the century of Turkey” in the May 2023 presidential election. Turkey, in the eyes of Erdogan and his supporters, has been deprived of its full potential over the last several decades, mostly by the West, but is now destined to be a consequential power in the new century.

Turkey’s leadership wants changes to the UN system and believes that it can play a political leadership role for the league of dispossessed – consisting of dozens of Middle Eastern, central Asian, and African countries that have been building economic, political, or kinship ties with Ankara.

At the same time, Turkey has been part of the West for much of the post-war period. It has been embedded in Euro-Atlantic institutions since the early 1950s, is a founding member of the Council of Europe, an active participant in NATO, and a candidate for EU membership. Its economy is intertwined with those in Europe and Turkey has economically and politically benefitted since the Marshall Plan from its place in the transatlantic community.

Today, the Turkish public and Turkey’s current rulers see these institutions and ‘transatlantic’ identity as an encumbrance, if not a trap. That does not, however, mean that Turkey wants a full divorce or can abruptly disentangle itself from the West. Ideally, Erdogan’s Turkey wants to have a foot in each camp, negotiating with great powers, running from NATO summits to Shanghai Cooperation Organisation meetings, all the while expanding Turkey’s economic and political interests.

A post-Western Turkey is able to instrumentalise the age of systemic rivalry by finding openings to satisfy its more revisionist instincts. Turks believe time is on their side – and that the world order will eventually create enough fissures for them to establish a more dominant regional role. In future, they intend to have a seat at the big table rather than live with the fear of being on the menu.

Indiastarts from a very different position from Turkey but ends up taking a similarly polyamorous perspective. India is not a revisionist state and has historically always played by UN rules. But that does not mean it is satisfied with every aspect of the existing international order. As the world’s most populated state, India believes it does not yet have a role and status commensurate with its actual economic, political, and military weight. The BRICS – which began as a counter-organisation to the G7, with India as a founding member – has gradually become institutionalised specifically to assert that claim. The Indian government has also refused to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or to apply sanctions on Russia.

Unlike most other members of that club, however, India was committed to a rapprochement with all members of the G7 even when the BRICS was formed. It sees the G7 countries as partners to its own rise. Its engagement with the BRICS in this sense is an effort to avoid systematically aligning with G7 partners, rather than an effort to disassociate themselves from the current world order. As former Indian foreign secretary Kanwal Sibal puts it, “India is only aligned to its national interest”.

Ultimately, India aspires to contribute to setting the rules of global governance. As befits a polyamorous power, Indian policymakers think of India as a pole in the international order and want the country to be recognised as such. From this perspective, considerations about the more or less multipolar character of the world are nothing but an assertion of India’s prominent status or, at the very least, of its aspiration to such a position.

Strategic interdependence

In this new, more fragmented world order, which is increasingly overtly transactional, Europeans need a strategy that stresses Europe’s connections with countries beyond the US in order to protect their interests with the range of other countries that are shaping power dynamics. Such a strategy would respect the sovereign desires of the other middle powers outlined above and simultaneously increase Europe’s own sovereignty. We call this approach strategic interdependence.

This should begin with a clear definition of Europe’s interests in the new order. The European Commission’s spring 2023 communication about a European economic security strategy sets these out as: to promote European competitiveness; to protect the EU from economic security risks; and to partner with the broadest possible range of countries that share the EU’s concerns or interests on economic security. The furtherance of these interests should be underpinned by a rules-based order, which provides a framework in which the EU – governed by a rules-based system – is able to operate. While it should privilege relationships with partners that share its values, the EU will need to coexist, and sometimes work, with other countries too. The rules-based order to this approach should keep the guardrails in place when managing this complex interdependence.

At its heart, strategic interdependence should therefore allow the EU to preserve its agency by building relationships with key players in which it preserves the power to stand up to them when they challenge its interests and values. This is not straightforward. One of the key reasons that many of the powers explored in this paper are pushing back against certain tenets of the current order is precisely because they perceive this to preserve the West’s dominance of this system.

Strategic interdependence is a middle way between strategic autonomy – which threatens to divide the EU and alienate the rest of the world – and full alignment with the US in an anti-China bloc. Where strategic autonomy aims “to act autonomously when and where necessary”, strategic interdependence acknowledges and emphasises the complex reality of our interconnected world. It advocates building resilience to the weaponisation of dependencies whether in the fields of migration, technology, or trade, but pushes back against the idea of decoupling. The “strategic” epithet acknowledges the fact that this interdependence is a double-edged sword, that relationships must reflect power dynamics and interests, and that Europe will be more successful if it looks for partners in crafting a post-post-cold war order than it will be if it overestimates the legitimacy of yesterday’s world.

Strategic interdependence should rest on three key principles:

Firstly, European policies should be informed by an understanding that, in an interdependent world, decoupling is not just unrealistic, it is likely detrimental to Europe’s interests if the rest of the world rejects the concept. There are areas where it will make sense to avoid excessive dependencies on potentially hostile countries (when it comes to critical raw materials, for example). But the urge to decouple should be restricted as much as possible in favour of de-risking and investing in building relationships with key middle powers.

Secondly, European foreign policy should focus on preparing for a world of political co-existence and competition. The EU should not assume that it can change the regimes in other countries – and will therefore need to live alongside them. Rather than making the world safe for democracy, the goal should be to make European democracies safe in the world. This effort must begin at home and EU governments should invest in programmes to compensate the losers of globalisation in Europe in order to avoid exacerbating political fragmentation.

Beyond Europe, they should also invest in supporting countries that are more affected by the global transitions in technology, decarbonisation, and demography. For example, the economic transformation that must accompany decarbonisation will imply changing dynamics in many of Europe’s relationships with its neighbours. Europeans should both explore joint responses – such as the co-development of low carbon technology – and continued dialogue about how European choices – such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – affect these partner countries. European countries should be prepared to support countries that are harmed by these policies as an investment in their longer-term relationships. This willingness to invest in supporting the losers of progressive policies, in order to cement partnerships, should also be applied to other fields.

Thirdly, Europeans should start looking for partners to build a new world order – rather than trying to preserve the old one. While it may be confidence-boosting to sit among like-minded states and agree on bilateral and plurilateral solutions to global problems, the bigger challenge now is to reach out to new partners on different issues. The recently announced IMEC is a perfect example of the sort of initiative Europe should invest more in. Expanding formats such as the Global Gateway and the EU Digital Alliance with Latin America hold equal promise.

Europeans should also consider whether older Western-dominated formats can escape irrelevance by including a wider membership. The EU should identify the domains (regulatory, standard-setting, or otherwise) in which it can apply its strengths to achieve solutions that work.

Overall, international formats must enhance, rather than destroy sovereignty. They should focus less on deregulation and more on strengthening national sovereignty. The ability of international institutions to reduce autocratic states’ room for manoeuvre is waning – but they can still play an important role in developing practical solutions to global problems in an age of competition. They can facilitate information sharing, manage escalation, and, ultimately, provide guardrails against conflict. The UN will not avert competition between the powers of the new order, but it can help manage it.

It is in the interests of all powers to make competition work for the collective challenges the world faces. But the EU as a hyper-connected power is strongly exposed to the decisions that the US and China make to manage their growing strategic rivalry. The EU therefore needs a more strategic approach to managing this interdependence to protect its own interests. In the field of climate, for example, multilateral approaches have achieved only modest emissions reductions in the past decades, but a new force does seem to be driving more rapid progress in the past few years – strategic climate change rivalry. Beijing and Washington are investing in smart grids, modern charging infrastructure, and new materials. They are also using economic coercion, such as granting or restricting market access, imposing import duties on goods that have not lowered their production emissions, and, in extreme cases, sanctioning the worst polluting entities. Reclassifying climate change efforts as part of geopolitical competition, on par with other national security issues, can also spur more timely action and help secure funding from domestic budgets for more drastic emissions reductions. Europeans should explore the potential to harness this type of competition to advance work in other areas.

Beyond these principles, Europe’s approach will need to be actor-specific and include individualised strategies that make the various players feel more sovereign. The categories of middle powers can provide some guidance on how do this.

The peace preservationists, whose main goal is containing the rise of China and preventing a war between the two superpowers, have many common interests with Europeans. Like them, Europeans do not want to have to choose between China and the US and want to maintain a functioning relationship with both sides. It is therefore vital that Europeans have multidimensional relationships with these countries that do not run through Washington. Europeans also need to move from a purely economic presence in the east Asian region to a more strategic relationship. The first step in this process is to show up at important regional meetings. The EU should consider joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, as the United Kingdom has, in order show that it seeks a responsible stakeholder role in the region. Furthermore, Europe should expand its security partnerships with these countries by taking part in defence dialogues and considering increased arms exports.

The America hedgers are keen to develop their links with countries other than the US. Europeans offer that potential, and indeed have their own reasons for engaging with these countries. Unlike the US, Europeans have to live with the direct consequences of what happens in the Middle East. Spillovers from terrorism and migration from the region directly impact European countries and European domestic politics. For this reason among others, European interests in the Middle East will sometimes differ from those of the US. The EU should therefore build its own collective approach to this region and become an independent player, not just America’s junior partner. In Latin America, the EU should also focus on bilateral regional initiatives. It should bring its free trade agreement with Mercosur to the finish line as soon as possible and seek opportunities to cooperate on technology and green energies – by expanding the Global Gateway and EU Digital Alliance with Latin America, for example. The EU also needs to demonstrate that it is in the region to form and strengthen its own networks of cooperation, and help countries reaffirm their economic and political sovereignty, not just to counter China.

With the post-colonial dreamers, Europe’s potential areas of cooperation include climate change, infrastructure, health, and international finance. In many of these countries, various European states have a lot of historical baggage. Europeans are likely to fare better in developing cooperative relations if they talk honestly about what their interests are in these areas of cooperation, showing that they are keen to be partners in a multipolar world in which all countries have agency. A moralising approach may be counterproductive with the America hedgers, but a more values-grounded dialogue might hold some benefits with the post-colonial dreamers – if carried out in a targeted manner, which identifies areas of agreement rather than broad commitments to ‘universal values’, and is backed up with concrete financial support. European actors should also aim to build the post-colonial dreamers’ confidence in partnership through productive talks about debt sustainability, compensation for loss and damages due to climate change, and vaccine intellectual property issues. Through the Global Gateway, the EU has a chance to become a key partner in Africa’s green transformation – to the benefit of both continents.

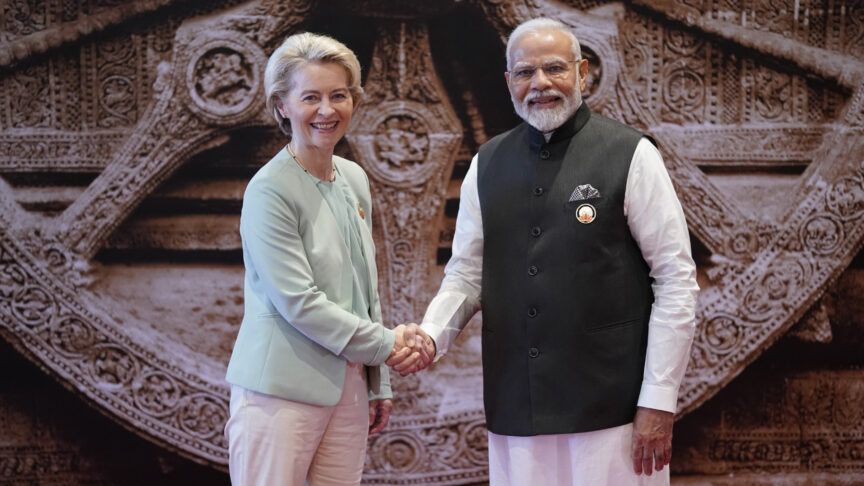

Finally, in their approach towards the polyamorous powers, such as India and Turkey, Europe must be especially clear-eyed about the transactional nature of any relationship. Europeans should therefore engage with them squarely on the basis of converging interests. Any cooperation with these countries will be temporary by nature and conditioned on a clear sense of mutual benefit. The IMEC provides potential in the fields of energy and infrastructure to build upon as an example.

In all cases, strategic interdependence requires a nuanced approach to cooperation. This begins from the understanding that coming to terms with the new reality of fragmentation cannot mean cutting Europeans off from the rest of the world. Instead, Europeans must engage constructively with non-Western players if they want to solve global problems and advance their own interests. It also does not mean an end to competition. But by being clear-eyed about European interests and capabilities, Europeans can leverage their still considerable heft to much greater effect. This will have more benefits for Europe and the world than a retreat into a cold war-style bloc.

About the authors

Asli Aydıntaşbaş is an associate senior policy fellow with the Wider Europe programme at ECFR and a non-resident fellow at the Brookings Institution. Her topics of focus include Turkish foreign policy and external ramifications of its domestic politics.

Julien Barnes-Dacey is the director of the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He works on European policy on the wider region, with a particular focus on Syria and regional geopolitics.

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and the director of ECFR’s European Power programme. Her topics of focus include strategy, politics and cohesion in European foreign policy; climate and energy, migration, and the toolkit for Europe as a global actor.

Marie Dumoulin is director of the Wider Europe programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. She has extensive experience with settlement processes of protracted conflicts in Europe’s Eastern neighbourhood.

Frédéric Grare is a senior policy fellow with the Asia programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations and a non-resident senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. His topics of focus include India’s foreign policy, Indo-Pacific dynamics, and maritime security.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of the European Council on Foreign Relations. His previous publications include “The Age of Unpeace: How Connectivity Causes Conflict” and “What does China think?”

Theodore Murphy is the director of the Africa programme at the European Council for Foreign Relations. He managed emergency response missions for Doctors Without Borders, in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Sudan. He has published and lectured on humanitarian issues writ large and specifically in the context of the Greater War on Terror.

José Ignacio Torreblanca is a senior policy fellow at ECFR and head of ECFR’s Madrid office. He is also a professor of political science at Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia in Madrid.

Acknowledgments

This paper draws on numerous conversations, friendly disagreements, and stand-up rows, involving so many colleagues across the vibrant ECFR community it would be impossible to name them all here. But the significant contributors to the creative process who have not emerged as authors include Anthony Dworkin, Jeremy Shapiro, Jana Puglierin, Vessela Tcherneva, Célia Belin, Janka Oertel, Camille Grand, Arturo Varvelli, and Piotr Buras. Anand Sundar has provided amazing research and writing support throughout the process, and Flora Bell thoughtful and methodical editing of what has at times been quite a chaotic piece. Both have improved the final output hugely. Despite these many different contributions, any mistakes are of course the authors’ own.