Despite Liberia declaring a three-year suspension of FGM, local and international human rights groups tell reporters that women and girls are still being persuaded through “its our culture” narrative and other times forced to undergo the procedure.

MONROVIA – Women and girls in Liberia are still being forced to undergo horrific female genital mutilation procedures despite a newly imposed nationwide ban and UN Human Rights Council strong resolution on the ‘Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation’ (FGM) human rights groups say.

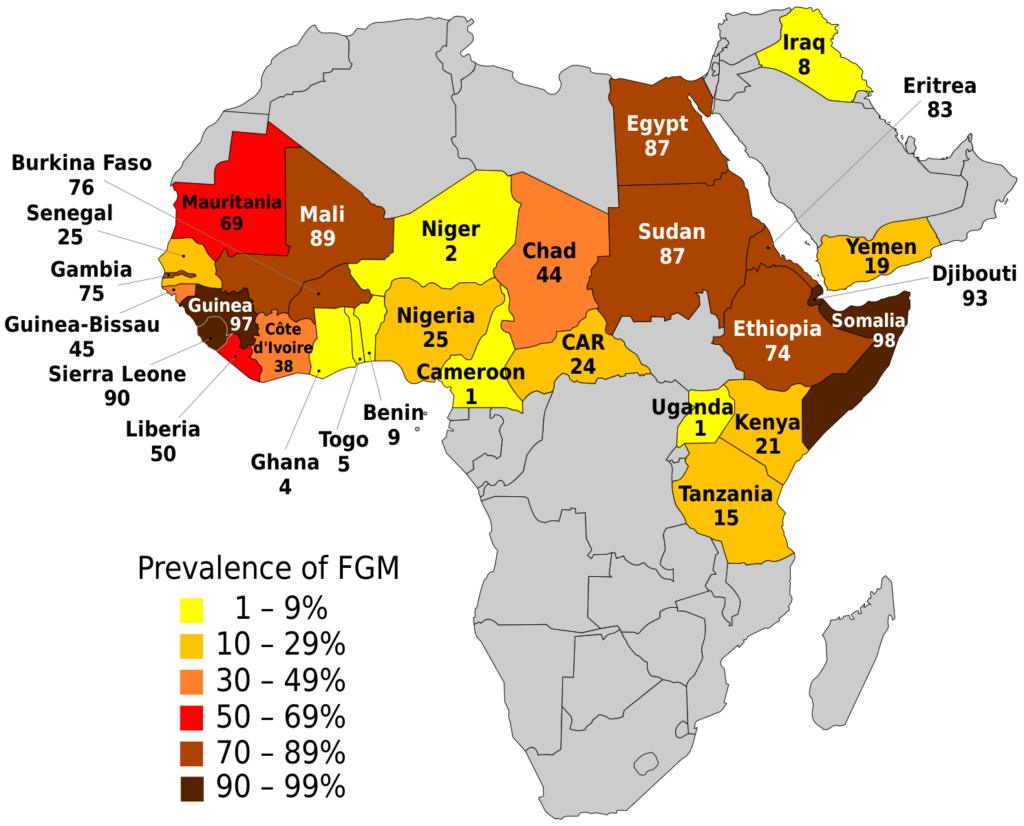

Nearly one third of girls in Liberia are subjected to FGM, a violent procedure in which all or part of the clitoris is cut off. In February, Liberia’s traditional council – a committee of the West African country’s most influential chiefs and traditional rulers – announced they would join the government in signing on to a three-year suspension of the practice, the longest ban on FGM yet.

But the suspension, which is not legally binding and comes with no punishment, has not been respected. In October, there was outrage after an 11-year-old girl was hospitalized for several days in the northern county of Margibi after bleeding heavily during an FGM procedure. While the case was condemned by civil society organizations across the country, Liberia’s traditional council continued to insist that traditional rulers were adhering to the suspension. But human rights groups told reporters they have heard reports of many similar cases in recent months.

“The ban that was announced is not working,” Esther D. Yango, the Executive Director at Women NGOs Secretariat of Liberia – a network of 104 organizations committed to ending violence against women and achieving gender equality in Liberia – told reporters. “Currently, we’ve had to provide money for medical support to victims… who were cut.”

FGM is common in Liberia, especially in rural, more traditional communities, where girls undergo the procedure as part of coming-of-age ceremonies. The practice – carried out by women called “zoes” – often takes place in secret locations known as “bush schools” where girls are enrolled and might spend months generally learning housework skills that their community believes they need to be officially regarded as women. In some cases, girls have been known to be forcibly enrolled into these schools against their family’s wishes.

In June, the UN Human Rights Commission reported on the case of a 15-year-old who was abducted by traditional leaders and forcibly initiated into a “Sande society” where she remained until her mother found her and paid $45 for her release. Her mother, Deborah Parker, is furious. “On the one hand I received justice because my daughter came back. On the other hand, I did not get justice because the women who abducted her were not prosecuted,” she told the Commission. “Although the Government said they would make them compensate me, I am still fighting for these women to be arrested and pay back my expenses. I lost the little money I had.”

While campaigners against the practice have made some progress in reducing the rate of FGM in Liberia, the practice remains prevalent. According to the World Bank, 31 percent of women in the country in 2020 had undergone the procedure, a drop from 44 percent in 2013.

So far, attempts by activists and human rights groups pushing for a permanent, legally-binding ban have been unsuccessful. In 2016, Liberia’s legislature removed portions of a domestic violence bill that sought an outright ban on the practice. Another bill is currently before politicians, but it appears to be a long way away from being taken up. One obstacle to a permanent ban is finding a way to replace the income and livelihood that many zoes will lose if the “bush schools” were closed down. To combat this, in 2021, the government, in collaboration with its international partners, launched an Alternative Livelihood Program that provides zoes with new life skills and resources to earn a living outside the practice.

Anti-FGM campaigners have had to accept short-term bans mostly done through executive orders. In 2018, on her last day in office, former president Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf signed an executive order banning FGM for girls under 18. A year later, current president George Weah extended the ban another 12 months.

According to Tamba Johnson, founder and national coordinator of He for She Crusaders Liberia – a local women’s rights NGO and a member of the civil society working group on FGM – the influence of the country’s powerful traditional societies have worked to block the implementation of a permanent ban. “FGM includes a lot of power dynamics,” Johnson told reporters. “In the rural areas primarily, being part of the [traditional society] is a thing of pride and zoes are also regarded with high authority.”

Esther agrees. “The ban is not working because political leaders lack the political will to end the practice,” she said. “We are going to elections next year and politicians are not pushing to end the practice because the traditional societies which conduct the practice have power, and politicians tap into that power in rural areas during elections.”

For Mackins Pajibo, Program Officer at Women Solidarity Incorporated, a women’s rights advocacy group based in Liberia, more needs to be done to spread awareness of the suspension.

“The ban has not been popularised,” Pajibo told reporters. “By popularised, I mean there has not been one on one dialogue with all the zoes. So what happens is that some people don’t know of the ban, or they hear it on radio and don’t think it is effective. Another reason however is that, there has been no major public repercussion for the reported cases of FGM that has occurred during the ban”.

Though progress has been made over the years, much work remains when it comes to ensuring gender equality and women’s rights in Liberia. As it stands, gender-based violence is widespread; Liberia ranked at 78 out of 146 countries in the 2022 Global Gender Gap Report. Additionally, women’s representation in Liberian politics remains low, at just 11 percent, 2021 World Bank data ranks the country at 164 out of 193 countries for proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments. It wasn’t until earlier this year that legislation was amended to allow mothers equal rights to pass on their nationality to their children

For Lakshmi Moore, combating FGM would also require the government to fix the “decades of neglect of public education infrastructure” that has seen “traditional schools remain as the primary pathway of education for women and girls.”

“In many of the communities where FGM is still prevelant, access to public education beyond primary school is limited, and poverty is endemic,” Moore said. “Tackling FGM… is no longer just the simple solution. Even if alternative rites of passage are supported and/or practitioners are provided alternative livelihood. We need to address the drivers of FGM and ensure girls have access to education, economic opportunities and can be protected from sexual violence.”

Source: VICE World News