Legend George Weah’s travels include cheering on his son Timothy at Qatar World Cup and attending multiple forums

When Timothy Weah scored for the USA against Wales last month at the Fifa World Cup, he sent American fans into rapturous delight as they celebrated their country’s first goal at the highest level of men’s international football in eight years.

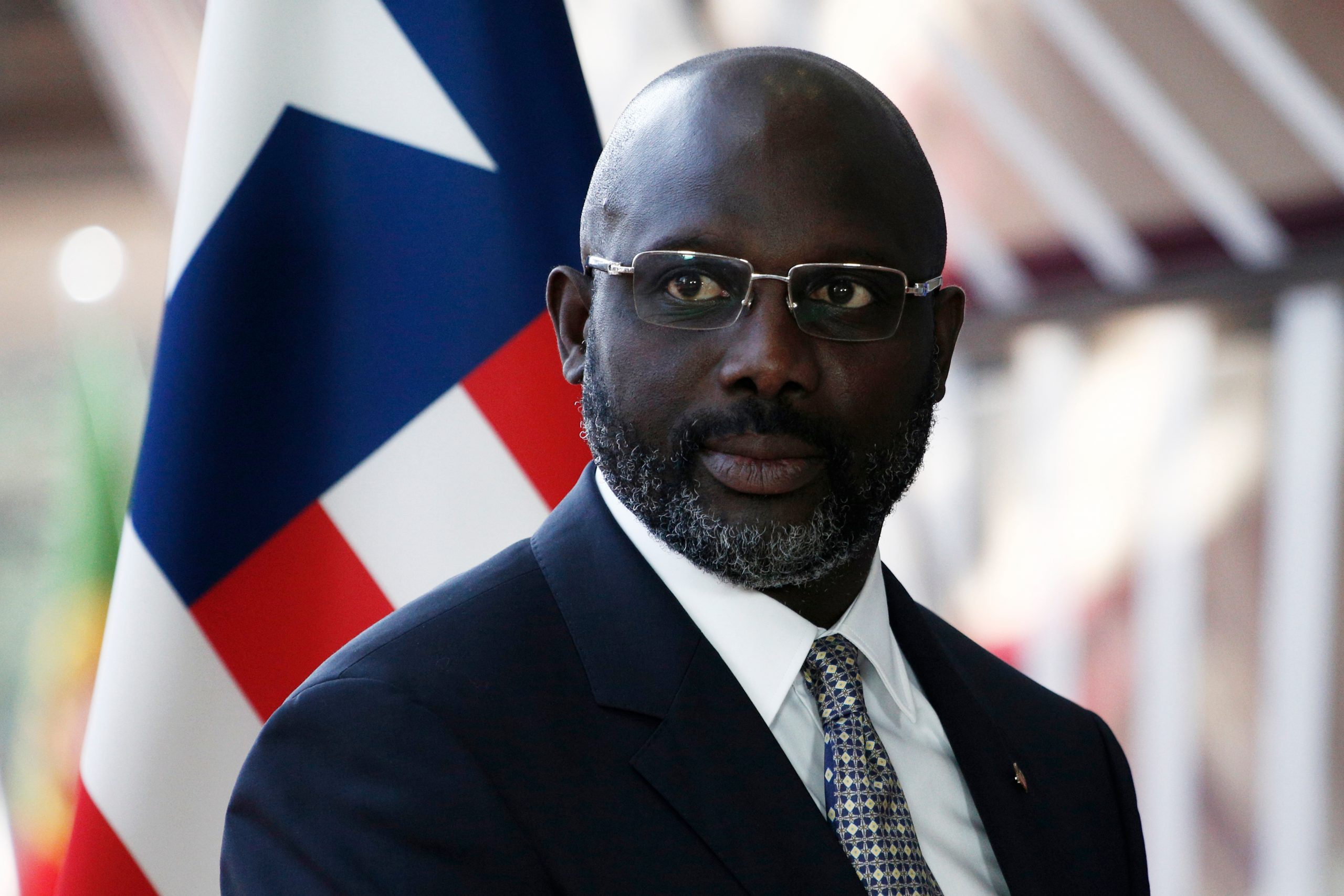

Among the happy throng at the Ahmad bin Ali Stadium was George Weah, father of Timothy. The elder Weah is a football legend who in 1995 became the first and only African footballer to win the Ballon d’Or, an annual award for the world’s best player, during a career that saw him play in the French, Italian and English leagues.

Weah wears a different hat these days, serving as president of the west African nation of Liberia — one of the region’s poorest countries and a former US colony — since 2018.

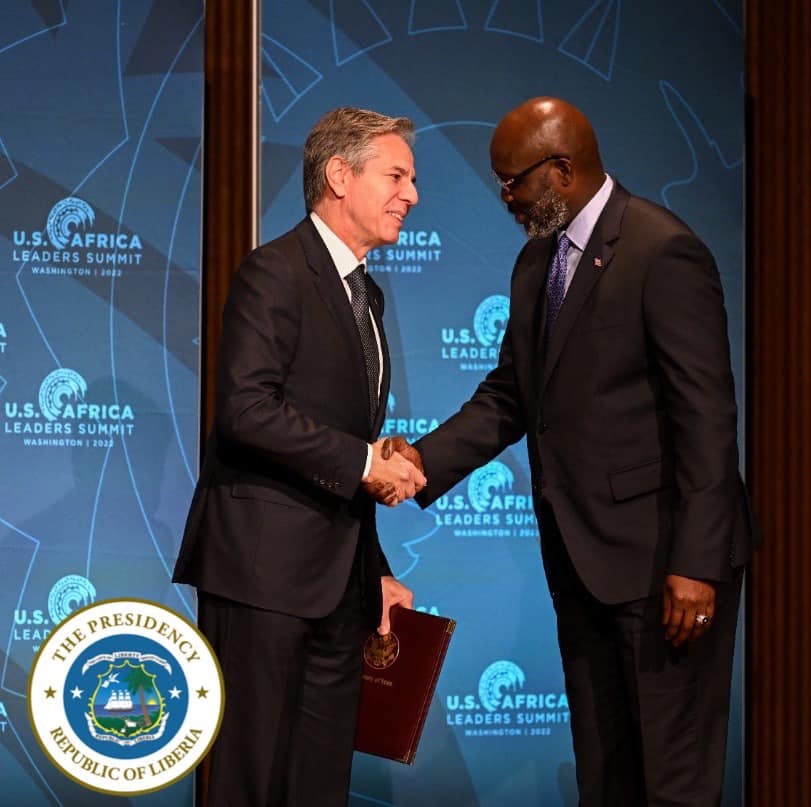

His trip to Qatar, part of a 48-day trip abroad that has included stops at forums in Morocco, Egypt and France and will culminate with his attendance at the US-Africa Summit, has attracted criticism from political opponents and civil society groups at home. Weah has been away from Liberia since November 1 and will not return until December 18. In a letter to the Senate explaining his absence, Weah said that justice minister and attorney-general Frank Musa Dean will chair cabinet meetings in consultation with the vice-president, Jewel Howard-Taylor, and “in telephone consultation with me”.

Weah’s office framed the trip as being in the country’s interests, pointing to his meeting with the Qatar emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani where he secured a verbal commitment for the funding of a highway in Liberia described as a “critical national infrastructure”.

But Weah’s opponents say his foreign travels offer no tangible benefit to his country and want the finance ministry to detail the cost to taxpayers. “We can’t find any political leader anywhere in the world who has stayed away for this length of time [for non-health reasons]”, says Alexander B. Cummings, presidential candidate of the Collaborating Political Parties (CPP), a coalition of opposition parties, which will face Weah in next year’s elections. “There’s nothing wrong with watching one game of a child, that’s an accomplishment, but to be in Qatar for that period of time and trips to Monaco is unbelievable.”

The cost of the trip is a point of contention because government officials are only funded for seven days of travel by law, with a daily allowance of $2,000 for the president as head of delegation. Weah is scheduled to be away for almost seven weeks. Finance minister Samuel Tweah says the president is not claiming funds from the public purse. Isaac Solo Kegbeh, a spokesman for Weah, told the Financial Times that Weah’s trips have been cost-effective, saying that his visit to the MEDays Forum, a Davos-type event in Morocco, was paid for by the king of that country. Kegbeh added that Weah also met officials from a steel manufacturer and Qatar’s Aspire Academy during his time in Doha. “The president is working in the interest of the country,” he said.

Analysts say the controversy over Weah’s travels is a metaphor for a presidency that has failed to deliver on key promises to root out corruption. Ibrahim Nyei, an analyst at the Monrovia-based Ducor Institute for Social and Economic Research, said: “Weah has not performed to the expectation of the majority of the poor people that elected him, he has significantly let the people down.”

Weah, a national footballing hero, was elected as a political outsider even as the country’s technocratic elite berated him for his perceived lack of polish and educational achievements. Ordinary Liberians identified with the player, mocked by the elite for his accent and style of speaking, a former government minister said.

But they added that the presidency has often seemed like a “distraction for Weah, a man who just wants to enjoy life” and that his performance in office has served as vindication for those who questioned his suitability for the top job. The former official described Weah as an “absent president”, adding: “Parts of the government that are working well are by chance. Usually it’s because the person running that department takes their jobs seriously.”

Liberia’s economy grew by 5 per cent last year, but its growth has been slower this year due to global uncertainties and commodity price shocks, according to the World Bank. With a GDP of $3.49bn, its economy is small and dependent on agricultural exports. Liberia is faring much better than its west African peers on inflation of 6.9 per cent but remains poor, with some of the worst social outcomes in the world, where many lack access to education and health services.

Corruption scandals have plagued Weah’s administration. In August, three senior government officials, including Nathaniel McGill, chief of staff to the president, were alleged by the US Treasury Department to have engaged in public corruption. Weah suspended all three officials after Washington imposed sanctions.

While Weah has been away, problems at home, including a faltering national census and funding crisis at the electoral commission ahead of next year’s vote, have rumbled on. “You need the president on the ground to organise meetings with the national stakeholders to address these issues; you cannot engage strategically when you’re abroad, “ said Nyei of the Ducor institute. “You don’t need the president engaging in meetings on the sidelines of events, the national crises are not being resolved.”

Source: The Financial Times