China is on a mission to break its dependence on Australia at all costs, but the superpower is leaving a trail of destruction in its wake.

China is on a mission to break its dependence on Australia at all costs, but a new report has revealed the superpower is leaving a trail of destruction in its wake.

One of the key ingredients it needs to fuel its ambitious growth plans to become the world’s most powerful and influential nation is iron ore, which is one of the main raw materials to make steel.

Australia is the biggest exporter of the red stuff which is mined largely in Western Australia’s Pilbara region and pumps an astronomical amount of money into the nation’s economy.

China is also the biggest consumer of iron ore — consuming a massive 61 per cent of the world’s exports — which it uses to make things like refrigerators and construction products.

Amid trade tensions and China’s plans to diversify its supply away from Australia, Beijing is determined to wean itself off our natural resources – but it has not been easy.

Because of the abundance and quality of iron ore in places like the Pilbara and problems hitting operations from other parts of the world like Brazil, China has continued to buy mountains of it from Australia.

President Xi Jinping has called this reliance a “strategic weakness” and his government have been busy trying to find another source.

Key to these plans is a mountain range stacked with iron ore in Guinea, West Africa — and a mega mining project there known as the Simandou mine.

The colossal mine’s potential is so huge that some commentators have suggested it could completely displace Australian iron ore production tonne for tonne or pump so much additional supply into the market that prices would fall off a cliff.

Either outcome would cripple Australia, which currently makes about $149 billion a year from the export.

There is an estimated 8.6 billion metric tons of ore buried in Simandou, which is enough to forge the Empire State Building 100,000 times over. The mountains are 2.5 billion years old, and experts believe their iron-rich ore is the largest and purest untapped deposit on the planet.

China is desperate to get its hands on the ore — which is collectively worth $1.1 trillion worth at today’s prices. There is enough ore in Simandou to build all of China’s airports, skyscrapers, cargo ships, and weapons for seven years.

However, trying to mine this ore and transport it to ships from the remote mountain range is a logistic and financial nightmare, and it has been plagued by allegations of bribery, military coups, legal disputes and an outbreak of ebola.

The mine – which has been the centre of turmoil and many mining rights disputes – is currently broken up into two main parts.

Anglo-Australian multinational company Rio Tinto has remained a major player since it discovered deposits there in 1995. Concluding it would be uneconomic to develop back in 2015, it changed its mind in 2020 as iron ore prices skyrocketed.

It now owns one half of the deposit with Chinese aluminium giant Chinalco and the Guinean government.

The other half had been held by companies with connections to Israeli mining giant Beny Steinmetz, who hammered out a multi-billion dollar deal with Brazilian major Vale, before they were stripped amid allegations of corruption against Mr Steinmetz.

The Guinean government then handed that half, in a tender, to a consortium of China-connected companies, including the world’s largest aluminium producer.

Their plans for the site are huge and they want almost all the ore going directly to China by 2025.

Last year, Chinese workers began cutting mining roads and blasting tunnels for a railway line the likes of which Guinea has never seen before.

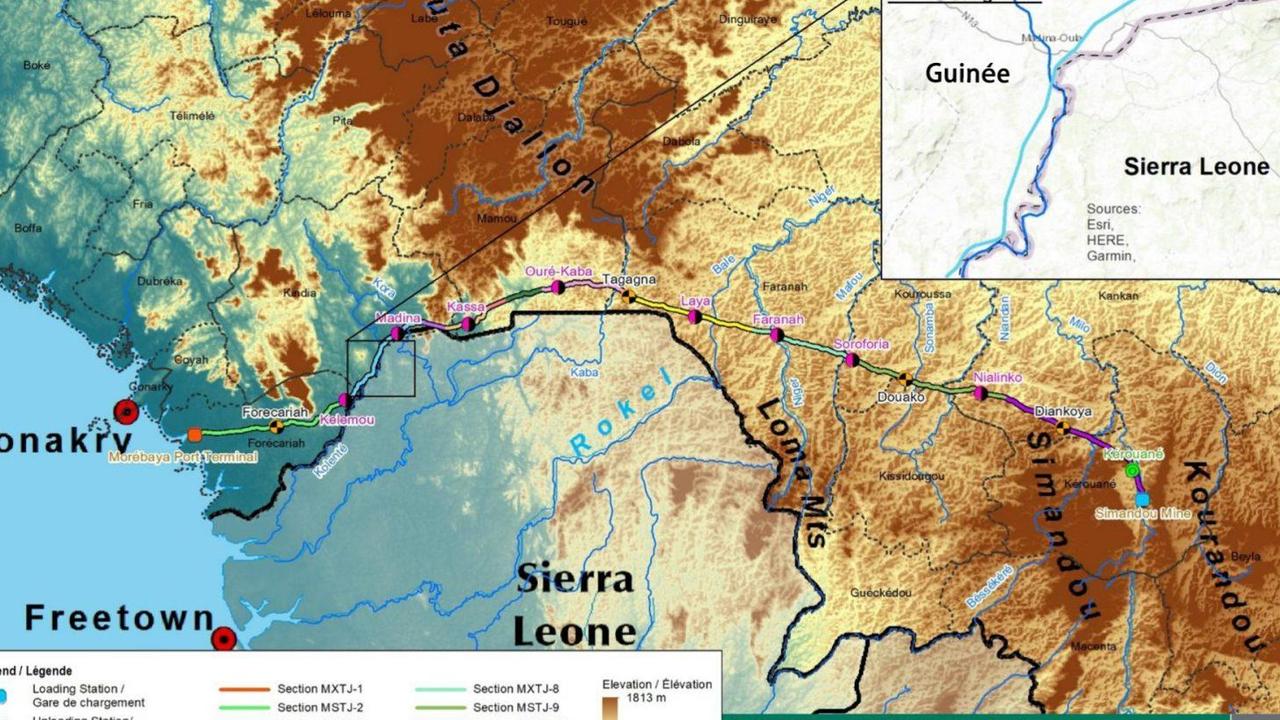

The $18 billion railway through the Guinean countryside would carry the precious ore from the mine to the future ore port of Matakong on the Guinean coast – some 679km away.

It could have taken a much shorter route to the sea through neighbouring Liberia, but the Guinean government insists it must go the longer route through Guinea to avoid passing through a neighbouring nation.

However, a shocking report from Bloomberg, written by reporters on the ground in Guinea, reveals a tense situation between angry locals who have seen their villages trashed, their water supplies polluted and their homes being blasted by dynamite.

According to the Chinese consortium the project affect at least 450 villages, many of which are intended to be “relocated” as part of the land acquisition and resettlement engagement activities.

In one of these villages, Bloomberg spoke to locals who said their homes had been damaged by dynamite blasts and that nobody is told when the explosions are going to happen.

Those who have been moved out said they were offered far less than their homes are worth. One farm owner said he was paid just 11 million Guinean francs ($A1791) for the farm where he grew pumpkin, peanuts, and coconuts, instead of the $200 million he estimates it’s worth.

Bloomberg reports that most people in the villages can’t afford to build new houses with what they received, and there’s no compensation for damaged buildings.

“We don’t have the ability to negotiate the compensation rate,” Abdoulaye Bangoura, a district chief, told the publication. “But we have to accept it, because there’s no place we can go to complain. These guys were brought in by the government, and the government isn’t a party you can negotiate with. You just have to accept it and live with it.”

Others said their water had been polluted with human waste and mining chemicals, their livestock had been killed by falling rocks, and that no economic or developmental benefits had filtered through to locals.

When Vale was prospecting it created jobs for locals hiring local people to handle waste or grow vegetables. But now villagers working for the consortium as drivers or security guards receive low daily wages rather than a salary, according to Bloomberg.

“To be honest, their economic benefit here is nothing,” Ansoumane Ziko Camara, the district’s liaison with the consortium told the publication. “Zero.”

The human cost is just one problem caused by the development which is also has environmental experts worried about the region’s 256 bird species, nine types of primates, and mammals including forest elephants and pygmy hippopotamuses.

The Chinese consortium behind the project includes China Hongqiao Group Ltd., the world’s largest aluminium producer and it is led by Winning International Group, a private Singapore-based shipping concern whose founder is from Shandong, China, the same province where the aluminium company is based.

Both are part of the SMB Winning Consortium which has been criticised by human rights groups for its practices in mining bauxite in Guinea’s Boké region.

Bauxite from Guinea now makes up a large proportion of the aluminium used across the world in car and aeroplane parts and consumer products like beverage cans and tin foil — but the effect on locals has been devastating.

Human Rights Watch reports that mining has had “profound human rights consequences” for the rural communities that live closest to operations.

“Mining companies take advantage of the ambiguous protection for rural land rights in Guinean law to expropriate ancestral farmlands without adequate compensation or for financial payments that cannot replace the benefits communities derived from land,” it reported.

“Damage to water sources that residents attribute to mining, as well as increased demand due to population migration to mining sites, reduces communities’ access to water for drinking, washing and cooking.

“The dust produced by bauxite mining and transport smothers fields and enters homes, leaving families and health workers worried that reduced air quality threatens their health and environment.”

The situation deteriorated so badly that riots broke out in Boké in April and September 2017, due to anger at inadequate local services, particularly a lack of water and electricity, resentment at the rapid expansion of mining and broader concerns about the impacts of mining on local communities.

Thousands of young people ransacked government buildings and erected informal checkpoints, preventing mining companies from operating.

“If frustrations accumulate, it can be anything that sparks the powder,” a senior ministry of mines official told Human Rights Watch. “The population sees the financial investment a company is making, they see taxes being collected, trucks taking bauxite from their farmland abroad [for export], they breathe the dust, and they ask, ‘what do we get out of it?’”

As the project to turn Simandou into the world’s most lucrative iron ore mining operation continues, there are fears that tensions could boil over once again.