Martina Johnson was allegedly involved in mutilations and mass killings during the first Liberian Civil War. Thirty years later, Johnson has yet to stand trial.

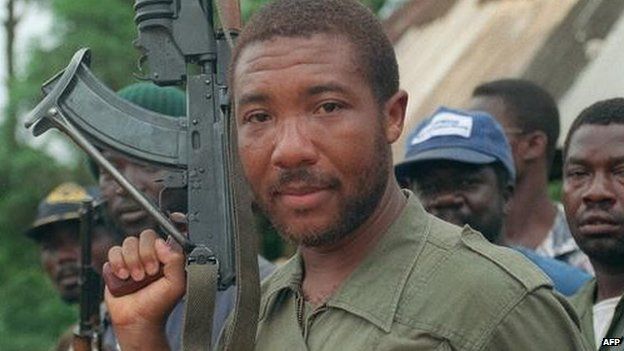

In October 1992, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) forced hundreds of mostly intoxicated child soldiers to attack Liberia’s Capital Monrovia. They were part of “Operation Octopus”, a four-month-long attack against Monrovia, during which thousands of inhabitants were killed, and hundreds of thousands displaced. Martina Johnson allegedly was instrumental in the planning and execution of the operation. The former NPFL commander was one of the very few female personal guards of the rebel leader Charles Taylor during the First Liberian Civil War.

Johnson has resided in Belgium since 2003. In 2012, Belgian human rights lawyer Luc Walleyn, collaborating with the Geneva-based NGO Civitas Maxima, filed a complaint against the former rebel commander before the Belgian Public Prosecutor’s Office on behalf of three Liberian victims. The alleged perpetrator can be sentenced in Belgium under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which states that particularly cruel crimes (genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity) can be tried regardless of where and when they were committed. Shortly after her arrest, she was placed on conditional release.

Eight years have passed since Martina Johnson’s arrest and a verdict is still nowhere in sight. Civitas Maxima has been investigating Johnson’s alleged crimes since 2011. “We are now 10 years after the initial complaint and there is no trial in sight as far as we know,” said Alain Werner, director of the NGO. “One alleged victim of Ms Johnson and several witnesses have already died, and nobody understands why this case is taking so long.”

Several state authorities have been to Liberia to investigate other war criminals since 2019, yet neither the Belgian investigative judge nor the prosecutor, who opened investigations first, went there. Johnson’s defendant told JusticeInfo that four out of five defense witnesses have died. “The damage is irreparable,” he complained.

Why it’s taking so long

Johnson can indeed be tried in Belgium under the principle of universal jurisdiction, but the country has had a difficult relationship with the legal concept. In 1993, the country passed a law that made it possible to prosecute the crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes committed abroad in Belgian criminal courts. This law made Belgium a leader in the struggle for international justice, according to Human Rights Watch.

However, when a group of Iraqis sued former US President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney and secretary of state Colin Powell for bombing an air raid shelter in Baghdad during the 1991 Gulf war, the US threatened to relocate NATO headquarters. In response, the Belgians changed the law: since August 2003, only people with Belgian citizenship or main residence in Belgium can be tried in its criminal courts through Universal Jurisdiction.

The lengthy duration of the case is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights enshrines the right of every person to a fair trial, which also includes a right to a trial “within a reasonable time”. Therefore, Johnson also has the right to a trial that is not excessively lengthy.

Furthermore, in a 2013 resolution, the UN General Assembly recognised the right of victims of gross violations of human rights to the truth about events, which includes the right to the identification of perpetrators. This right was also recognised by the European Court of Human Rights in numerous cases (for example, in El-Masri v the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). In the case of an investigation lasting ten years and pending, this right of Johnson’s numerous alleged victims should be taken into consideration.

Johnson’s case reveals the problematic side of international criminal law cases before state courts. Only the most terrible crimes can be tried through the principle of universal jurisdiction. Impunity for these crimes is particularly hard to bear for the victims. Yet, national authorities are hardly trained to deal with international cases, and proceedings are often too long – perhaps because the courts fear high costs, or the national prosecutors and investigators lack relevant training to deal with crimes that were committed long ago in distant countries.

Alain Werner demands swift action in order to protect Martina Johnson’s numerous alleged victims: “Before the evidence completely disappears, the relevant Belgian judicial authorities need to urgently conclude the investigative phase and decide whether or not Ms Johnson will stand trial, and if so when.”