-Build Back Better World Initiative launched at the G7 is unlikely to dislodge Chinese dominance in the continent’s infrastructure drive

-The new funding programme is likely to focus on ‘soft’ projects like climate, health and security, rather than dams, roads and railways

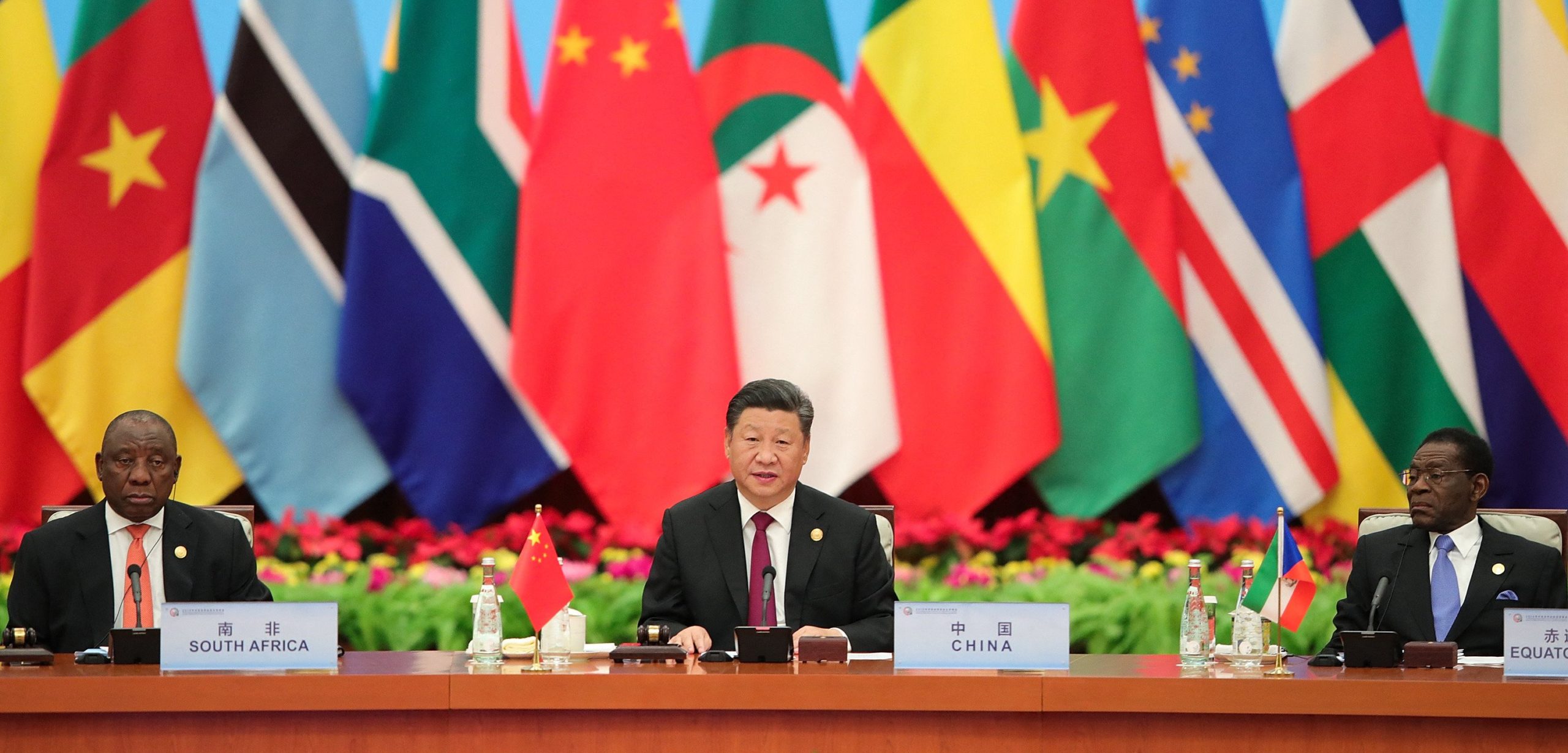

US President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better World initiative (B3W) may complement rather than counterbalance his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping’s transcontinental infrastructure funding project.

The B3W, which aims to invest US$40 trillion in developing nations including Africa by 2035, has been framed by the US as a “values-driven, high-standard, transparent and climate-friendly alternative” to the Belt and Road Initiative.

But observers say the B3W – launched by the leaders of the world’s richest democracies at the G7 summit in June – and the belt and road programme have very different goals and approaches.

“B3W relies on mobilising private sector capital while BRI is largely financed by loans from Chinese state-owned institutions,” said David Shinn, a professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.

And while the belt and road initiative is “focused on hard infrastructures such as roads and dams … B3W emphasises soft infrastructure such as climate, health and security, digital technology, and gender equity and equality … The only real overlap is in the communications sector”, he said.

“There is plenty of room for both B3W and BRI if they are implemented appropriately.”

Last week 10 projects were identified for B3W funding, during a visit to Ghana and Senegal by a US delegation led by deputy national security adviser Daleep Singh. It followed a similar mission to Colombia, Ecuador and Panama in early October. Another is planned for Asia before the end of the year, according to a senior US official quoted by Reuters.

While in Senegal, the delegation also visited the Institut Pasteur Dakar vaccination manufacturing facility and a cold chain warehouse, recipients of financing from USAID and the United States International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), respectively.

W. Gyude Moore, a senior policy fellow with the Centre for Global Development and a former Liberian public works minister, said the US was likely to invest in energy and health projects in the two African countries. “In Senegal, I know they will invest in vaccine manufacturing. I suspect it’s not the only health-related investment they will make,” he said.

Moore questioned the assertion that B3W would focus on “quality projects”, saying he did not expect the two initiatives to be that different. As an example, he pointed out that until 2019, rural telecommunications companies in the US had used Huawei equipment. “So if their quality was good enough to be used in the US, I can’t see why they would suddenly not be good enough,” he said.

“I think the difference will be in the transparency of the agreements and a more prominent role for the US private sector, as opposed to Chinese state-owned entities (SOEs). It is yet unclear whether B3W will also invest in rail, roads and ports. They are not listed as investment targets and these are the areas of focus under BRI.”

Moore said it would be in African governments’ interests to diversify their funding sources. “Competition between B3W and BRI will be a good problem to have.”

China currently dominates in Africa’s hard infrastructure investment, including dams and railways – areas in which US and European companies have been hesitant to put their money in the past, unable to secure financial backing.

China’s foreign ministry on Tuesday downplayed the impact of B3W funding, saying “there is wide room for global infrastructure cooperation and various initiatives don’t have to counter or replace each other”.

In a swipe at the US, ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin added that “countries should work to build rather than tear down bridges, promote connectivity rather than decoupling, seek mutual benefits and win-win results rather than isolation and exclusiveness”.

The model for financing big infrastructure projects such as ports and power dams could be the differentiator between the two initiatives. A road in Kenya paints the picture.

Before president Donald Trump left office in January, the US had ambitions to build a 473km (293 miles) highway between the capital Nairobi and the port city of Mombasa. It would have run parallel to the US$3.2 billion Standard Gauge Railway, funded and built under the Chinese initiative.

When Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta visited the White House in 2018, he and Trump issued a joint statement welcoming the proposal by US engineering and construction firm Bechtel Corporation to build “a modern superhighway from Nairobi to Mombasa”.

But Bechtel and Kenya differed on financing terms. The company rejected Kenya’s proposal for it to build the highway and recover its money through tolls. Instead, Bechtel pushed for the Kenyan government to directly fund construction.

But the public-private partnership (PPP) model rejected by the US firm has become popular among Chinese contractors. In Kenya, China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) is building a 27.1km expressway for US$668 million that will link the country’s main airport and central Nairobi. It will recoup its investment by charging toll fees for 27 years.

Analysts warn that traditional funding models may not work, with financing challenges – as seen in the Kenya highway proposal – threatening to complicate B3W.

Tim Zajontz, research fellow with the Centre for International and Comparative Politics at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, said Chinese firms were “extremely cost-competitive” in the African infrastructure and construction markets because of their lower mobilization costs and longer investment horizons. “So beating Chinese firms in terms of pricing will remain a challenge for Western firms.”

Zajontz, who is also a lecturer in international relations at Germany’s University of Freiburg, highlighted the Biden administration and G7 emphasis on the B3W’s supposed competitive advantages over the belt and road scheme – notably transparency, local project ownership, high-quality standards, sustainable project finance and development.

“By explicitly framing the B3W as a more sustainable and equitable global infrastructure initiative, Biden is promising no less than ‘win-win proper’. Yet, the extent to which such promises will materialize depends not least on governance dynamics in countries where projects are implemented,” he said.

Considering the dire fiscal situation of many African governments, both initiatives would have to increasingly mobilise private equity investment, combined with state grants and guarantees, he added.

Zajontz said the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow had shown that B3W is now central to the Biden administration’s efforts to green the world under US leadership. “The transformation of the global economy away from fossil fuels will be a trillion-dollar undertaking over the next decades.”

Benjamin Barton, an assistant professor at the University of Nottingham’s Malaysia campus, said the greater test for B3W related to the ownership of ideas behind projects. If B3W relies on the traditional Western approach to development financing – where projects are built for “recipients” – it will not garner much traction, he says.

“One of the BRI’s greatest assets is the say it gives to local elites in determining the project type, rather than these elites only being expected to play a passive role.”

Barton said the belt and road programme, for all its flaws, remained attractive because of a business formula that includes competitive financing, construction expertise, labour supply, short project turnaround, bureaucratic efficiency, greater local input in project selection, cheaper sourcing of construction materials and a greater propensity for financial risk-taking – a proven good fit for the infrastructure needs of emerging countries.

According to Barton, it appears the B3W emphasis will largely be placed on climate-friendly infrastructure projects to help meet global climate targets, through the provision of a modicum of concrete green-friendly projects on the ground.

So far, the US$4.7 billion financing for an LNG facility on Mozambique’s Afungi peninsula remains the largest direct loan in the Export-Import Bank of the United States (Exim)’s history in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Moritz Weigel, founding director of the Germany-based firm China Africa Advisory, said a focus on communications infrastructure, energy (renewable energy) and health would seem plausible. However, transport infrastructure would probably remain limited to some flagship projects.

Weigel added there was room for both funding initiatives in Africa, since the continent has tremendous infrastructure needs and plenty of opportunities for realising commercially viable projects that are in line with international standards.

“Ideally, African countries will make use of them in a complementary manner. If there is competition, decisions should be taken on a case-by-case basis, guided by project-specific as well as broader socio-economic benefits and environmental sustainability considerations,” he said.